An Immense World

Lately, I've been reading An Immense World by Ed Yong. It's been a refreshing antidote to doomscrolling about whatever he-who-shall-not-be-named is up to today. Every page of his book draws you deeper into mesmerizing stories about non-human perception, revealing how astonishingly diverse sensory experiences can be across the animal kingdom.

We humans rely on five senses—sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch—to navigate the world. These senses shape where we feel safe, how we determine what's edible, and more. We just never really think about it that way. Yong challenges us to step outside of our sensory bubble to imagine the world through the experiences of other creatures.

Did you know that butterflies taste with their feet? That mallard ducks have a 360-degree field of vision? That catfish are essentially swimming tongues with taste receptors all over their bodies? Or that flowers reveal hidden patterns visible to bees but invisible to us?

Page after page, Yong illustrates how each animal has its own sensory world—its umwelt (or umwelten, plural)—often existing beyond our human comprehension.

Tuning into the umwelten around me today

One of Yong’s key points is that animals aren’t deficient for lacking senses we have—they’ve simply evolved to perceive the world in ways that meet their own unique needs. Take bees, for example: they can’t see red the way we do, but they can see ultraviolet light. For bees, this reveals unique patterns on flower petals, invisible to us, that guide them to nectar, which is sugar that provides them with the energy to fly.

Today, I had the chance to tune into the umwelten of the creatures I share the city of Burlington with. As part of the Vermont Master Naturalist program, I joined Alicia Daniel and Sophie Mazowita for a winter field day focused on wildlife tracking and tree identification.

We couldn’t have asked for better conditions. A few inches of fresh powder fell overnight, with the snow tapering off just before sunrise. Around 10am, under a gorgeous bluebird sky, Burlington was shimmering as bits of snow gently blew loose from the treetops. We set out into the woods at Leddy Park, and later Ethan Allen Homestead, eager to see which creatures had left tracks for us to find in the fresh snow over the past few hours.

Never write off a squirrel

About twenty feet from our morning rendezvous point, we stumbled upon our first set of tracks. (Pro tip: don’t join a group of curious naturalists if you’re hoping to cover a lot of ground quickly…)

Sophie encouraged us to start by observing the tracks—taking note of their size, shape, and orientation—before interpreting them: What direction was the animal moving? Which species could it be? She explained how cultivating sharp observation skills and staying open-minded is crucial to decoding animal tracks in the snow.

These particular tracks revealed a bounding (i.e., leaping) pattern, with two telltale pairs of prints (the front and hind feet). The size of the prints and the trails connecting tree to tree pointed us to an eastern gray squirrel, bounding through the fresh snow in the past few hours

We learned how slight differences could tell different stories: smaller but similar tracks would belong to a red squirrel, while a subtle shift in the orientation of the feet might signal prints of a flying squirrel.

Tracking isn’t just about footprints. Animals leave all kinds of signs of their movements if we tune into their umwelt, not ours. Sophie showed us “squirrel stripes” on the base of some trees—spots where squirrels chew on the bark and rub their cheek glands, leaving scent messages for each other. It’s like the “coffee shop bulletin board” for squirrels, Sophie said.

I’ll never dismiss a squirrel as ordinary again—learning how they navigate the world invites us to step outside our human-centric sensory bubble.

A springtail surprise

In addition to observing tracks and other signs of wildlife, sometimes looking closer—literally—can reveal stories in the winter woods.

Take snow fleas, for example. These tiny creatures are often overlooked unless you use magnification. Unlike the parasitic fleas you might be familiar with, these harmless arthropods—also known as springtails—hop around in the snow on warm winter days. They live in the soil and emerge into the snow, often found clustered within animal tracks.

A special shoutout to my friend Braden DeForge, who captured them with his iPhone macro lens in the video below:

Not only mammals leave tracks

It may seem obvious, but we were caught off guard today: not only mammals leave tracks. When tracking animals, following a set of prints for a while can help you gather more clues about who made them.

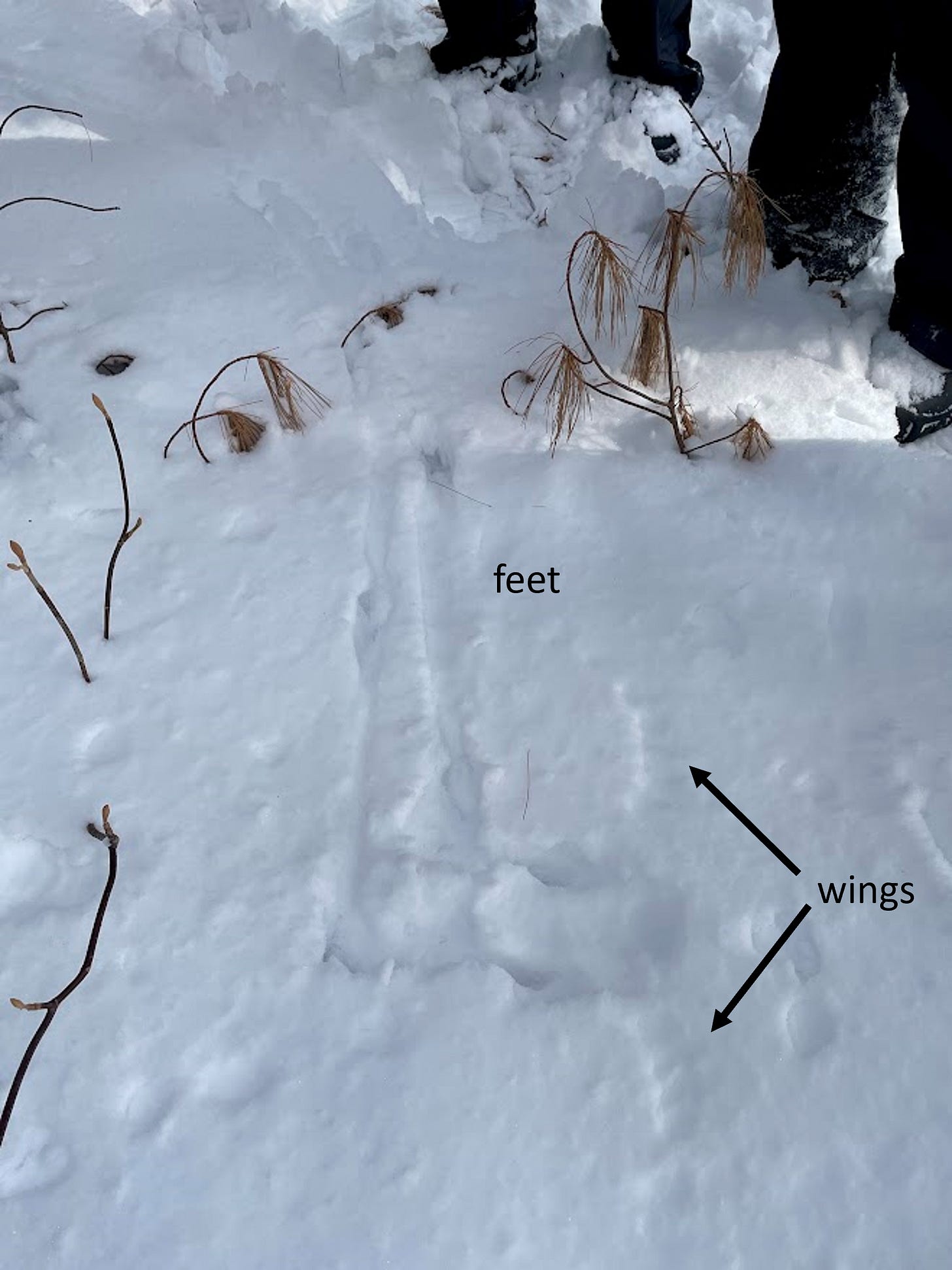

We were following a trail of prints through the woods at Leddy Park when we hit a dead end—literally. The tracks just disappeared at both ends of the trail. How could that be?

Birds!

It’s easy to forget that our umwelt is biased toward creatures that walk on the ground—not those that fly.

One end of the trail we were following led to two distinct arched prints. At first, we were stumped. Whose feet could make tracks like that?

Then, it clicked—wings! Not all prints in the snow are feet, that’s a human-centric assumption.

We’d stumbled upon evidence of a bird, likely a crow, swooping down to the forest floor, perhaps searching for a snack beneath the fresh snow.

Once again, tracking the creatures around invites us into another sensory realm and provides a humbling reminder that we are not the only ones using these woods.

The drizzle castle tree

To weave together winter tree identification with tracking, Alicia gave us homework for today’s field day. Each person was assigned to a tree and asked to look up a few facts about it, to be ready to share about the tree we came across it in the woods.

Hackberry was a new tree for me today. It’s one of those things that once you know what it is, you begin to see it everywhere. It has a very distinctive bark, described scientifically as having “wart-like protuberances.” Other, more pleasant descriptors our group came up with included the bark’s resemblance to 1) the Badlands National Park and 2) a drizzle sand castle.

One of my fellow naturalists is from South Dakota, so the Badlands thing totally worked for them. Having grown up playing in the sand on New England beaches, drizzle castles really hit home, and I will now never forget hackberry—the drizzle castle tree.

A friendly reminder that even as humans with the same five senses, we all have different, and perfectly valid experiences and perceptions of the world around us.

Who is living in my backyard?

In the summer, my morning ritual involves checking on my garden from the window at the top of the stairs. Bleary-eyed, I take in how it changes from day to day—tomatoes ripening, beans climbing their trellises, zinnias abloom—and then I scurry downstairs and out into the backyard to get a closer look. I love paying attention to how everything changes daily.

But today, after spending the day learning about winter ecology in Burlington, I realized I hadn’t been paying as much attention to the backyard lately. Covered in snow, the garden is dormant, and I had been operating under the assumption that—other than squirrels feasting at the bird feeder—not much is going on out there.

This evening as I peeled off my snow clothes and glanced out the window, I noticed something that I had not observed before. Besides the familiar squirrel tracks, there were other prints leading toward the shed. From the size and pattern, I think they belong to a cottontail rabbit bounding over to the shed looking for a cozy shelter during the snowstorm during the early hours of this morning.

I am always grateful for how this naturalist training sharpens my attention, expanding my own umwelt, to help me better appreciate the happenings in my own backyard.

All photos are mine unless otherwise noted.

Bonus cool thing!

Leave a comment if you know what this is and why it’s so interesting to find in the Vermont woods.